This is your brain when you change your mind.

“The “change-of-mind” behavior offers a window into how the brain uses the past, present and future to make decisions.”

Last updated: Nov 13, 2025.

Have you ever been taking a multiple choice test and gone back to change an answer after more deliberation (e.g., from A to B)? Have you ever picked up an item from the shelf in the grocery store, then put it back right after? My first grad school paper is on this topic - a change of mind. What happens in your brain when you have such a change of mind? Is switching your choice from A to B actually helpful in your next exam? Let me give you some answers in this blog!

The dataset

Between 2022 and 2024, I trained 5 rats in a maze with 4 outer arms (1 meter each) and a home arm radiating from a central platform, all leading to a milk port. Milk was always delivered in a specific order across the 5 milk spouts. I wanted to see if they could figure out this milk delivery pattern and if so, what is the neural mechanism behind it? If so, what is the neural mechanism behind it?

Initially, I trained them to alternate between going back to home and outer arm milk locations. Once they had learned to alternate home vs outer arms, I upgraded the milk delivery pattern to be: Home - Well3 - Home - Well4 - Home - Well2 - Home - Well1 - Home - Well3, in a continuous loop. Of course they are not aware of this pattern initially, but after 2 weeks of hanging out in this maze, they all figured it out as their running patterns predominantly match this pattern, without redunduncy of other well visits outside of this pattern. Their motivation to find this pattern could be to maximize the milk they get. The initial plan of my PhD study is to use this dataset to study how the brain extracts patterns from memories. See more in this blog post.

Rats show “change-of-mind” behavior

However, I observed something unexpected that sent me in a new direction: when foraging for milk, rats often change their mind half way down an arm.

This is something other projects in the lab also observe but the frequency in this task is way higher – up to 20% of attempts have changes of mind in some rats. There are multiple reasons why my rats do this more than others: first of all, my rats are good students who take things seriously/. Secondly, I use a very large maze scale where the outer arms are 1m rather than the shorter 50cm ones typically used in the lab W maze. This large maze set up creates a larger cost for wrong choices, potentially forcing the rats really think hard about each choice. Finally, rats are given sufficient time to complete a set number of trials rather than a set duration to complete as many trials as possible. This allows them to take the time deliberating each choice if they need to.

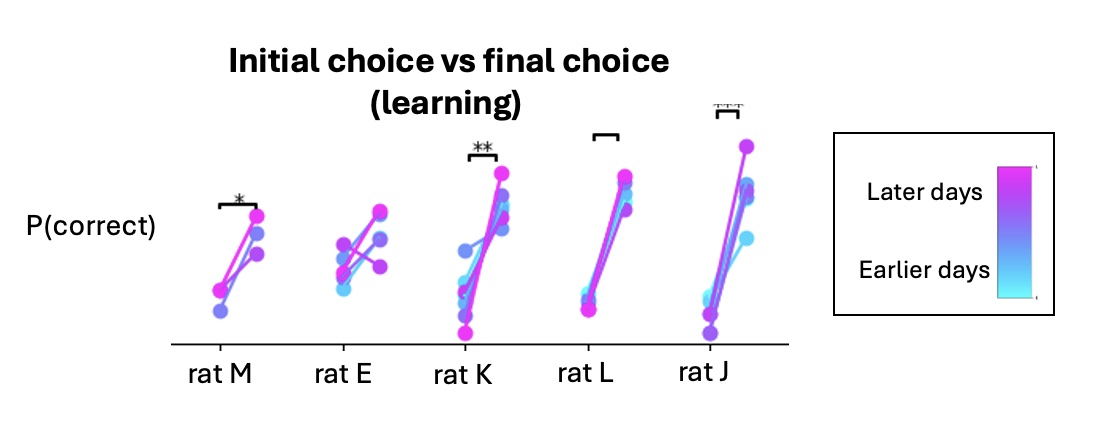

“Change-of-mind” behavior is generally corrective

This project is not the main focus of my PhD work, and it started as a small data exploration during a holiday break with no expectations. One of the first things I was curious about are whether the rats were better off keeping their initial choice or changing their mind. It turns out across all rats and all sessions, the choice after a change of mind has on average better outcome.

Each day, the rats ran 4-6 sessions of 30-60 min each, with naps in a separate area in between.

From the plot we see that the final choice is better on average. All these efforts to change their mind are worth it! There is more to the story. We analyzed the rats’ long-term behavior changes in this maze and found that this increase of correct rate has something to do with the animal overcoming their foraging bias. Please see the final paper for this detail.

Remote representations in the hippocampus follow stopping

The hippocampus is a brain structure that is very important for memory formation and retrieval; it is also a brain structure critical for maintaining a so-called “GPS” signal — a sense of where you are physically in a space. Recently, evidence has suggested that the hippocampus may also play a role linking the hippocampus to planning into the future (see here, and here).

In neuroscience terms, the hippocampus has been linked to predictive coding and mental simulation. In simple terms, the “predictive coding” part says that before an animal does something, you can predict what the animal is about to do next (to some extent) from the hippocampal neural activity; the “mental simulation” part is a mellower version that says before an animal makes a choice, you can read out the few options the animal considered rather than just the specific choice the animal picked. In summary, the field is grappling with how the hippocampus decides to encode where you are now, what you are about to do next, or your past, and how it serves you altogether to help you make smart choices.

This is the point where I realized this project is not a side project after all — the “change-of-mind” behavior offers a neat window into the mix of now, past, and the future. During a change of mind, does the hippocampus forgo being a GPS and present another option or other options, prompting the rats to change their mind? What is going on in the hippocampus when the rat is actively leaving the initial choice before committing to another one? In the exam analogy, what is going on in the hippocampus while I morph A to B?

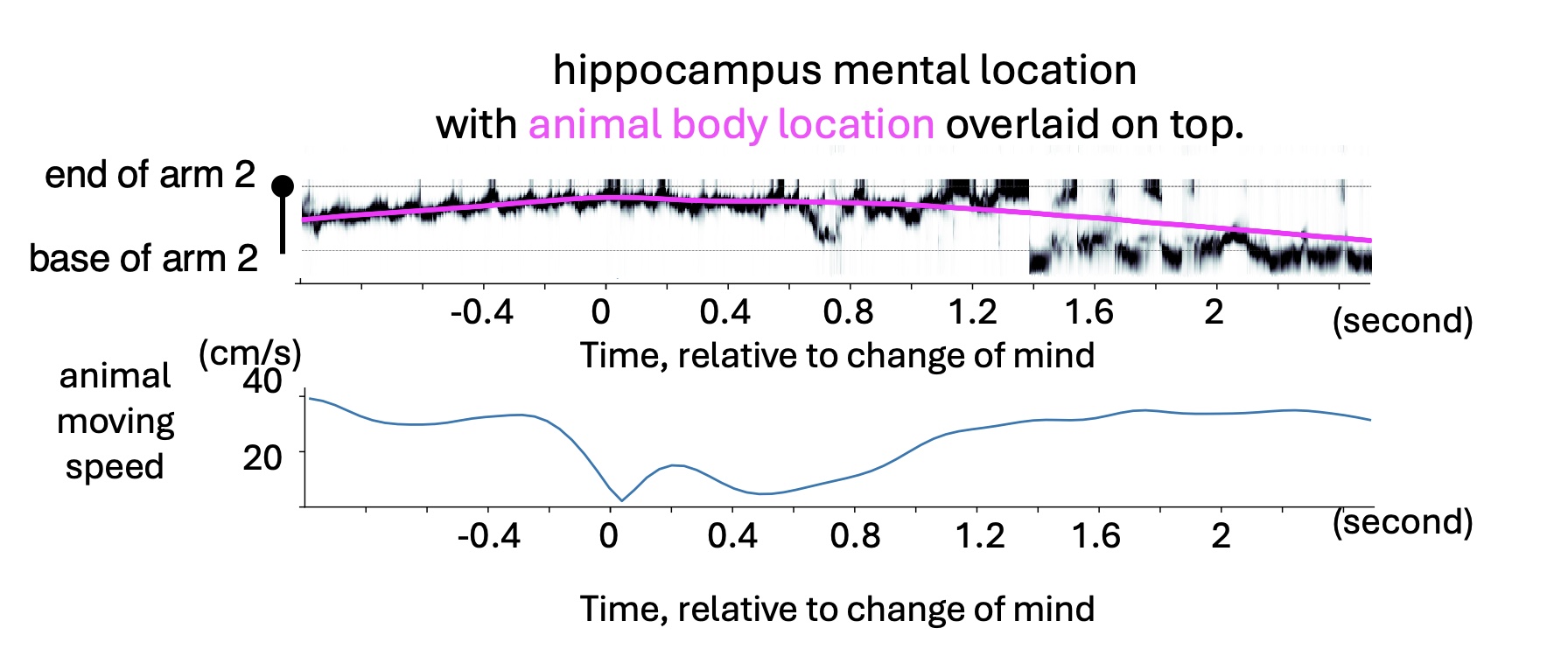

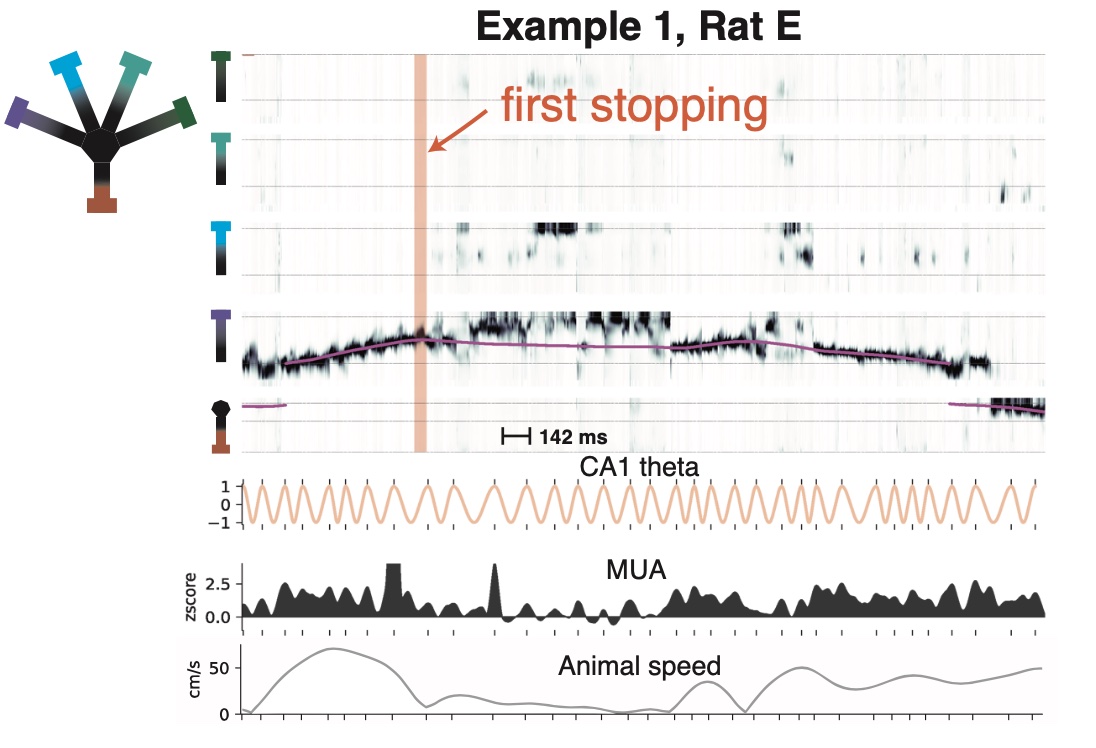

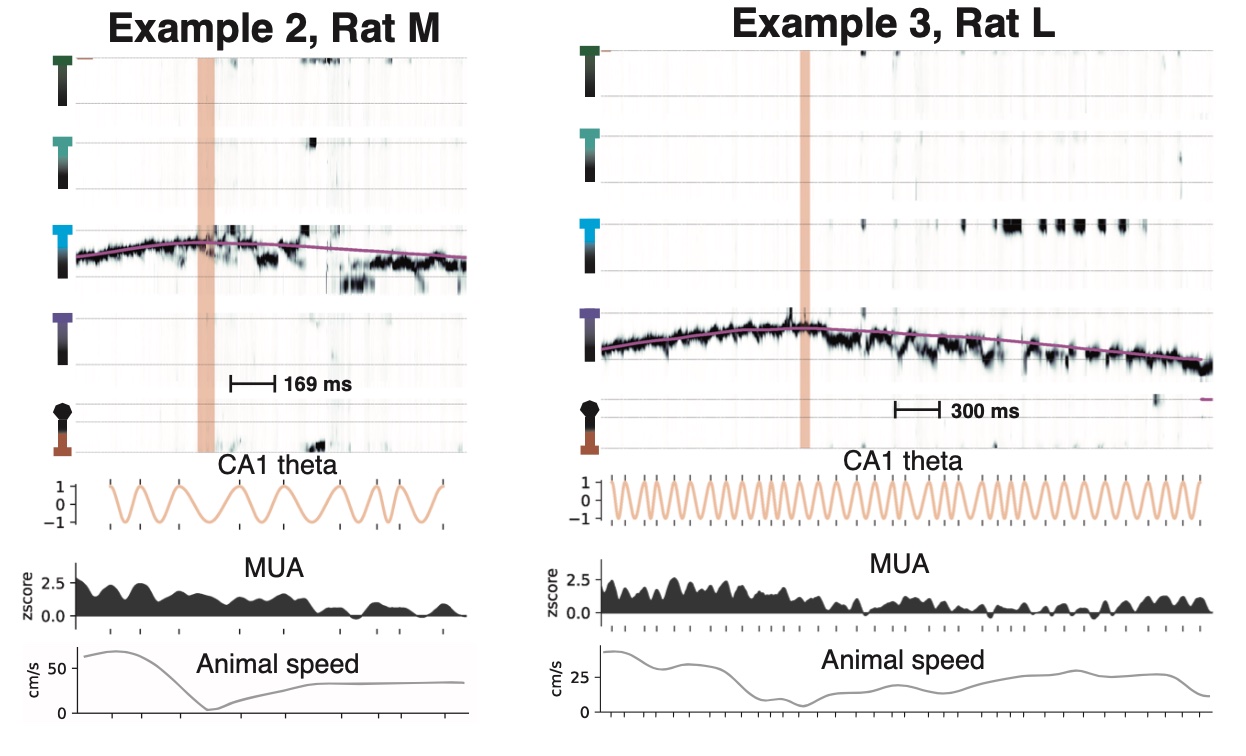

To study this, we assume that the hippocampus encodes the GPS signal when the animal is running and create a map that takes in animal body location and returns the average hippocampus signal. We then apply this map in reverse. This reversed function takes in specific moments of hippocampus signal and returns an estimate of the animal body location. If that the moment the hippocampus signal deviates a lot from the usual GPS signal, the estimated body location will not track the actual animal location. It is a mouthful to explain, and it might make more sense to see the plot directly:

The video on the left shows a 2D version of a static plot. Magenta denotes where the rat is and the little line on top shows its head direction. The blue/green/yellow shades show the estimate of the animal location from its hippocampus signal, with brighter color denoting regions of higher confidence of the inference.

To our surprise, there is little loss of GPS signal before a change of mind, defined by animal abruptly stopping on an arm before backing off or turning around to go to another arm. Instead, the hippocampus actively simulates going towards the end of the arm while actively leaving the arm — a mental simulation of what could have been if the choice was not changed.

There is more to the story. It turns out this counterfactual trajectory is packed in a specific temporal pattern – theta rhythm (~8Hz).

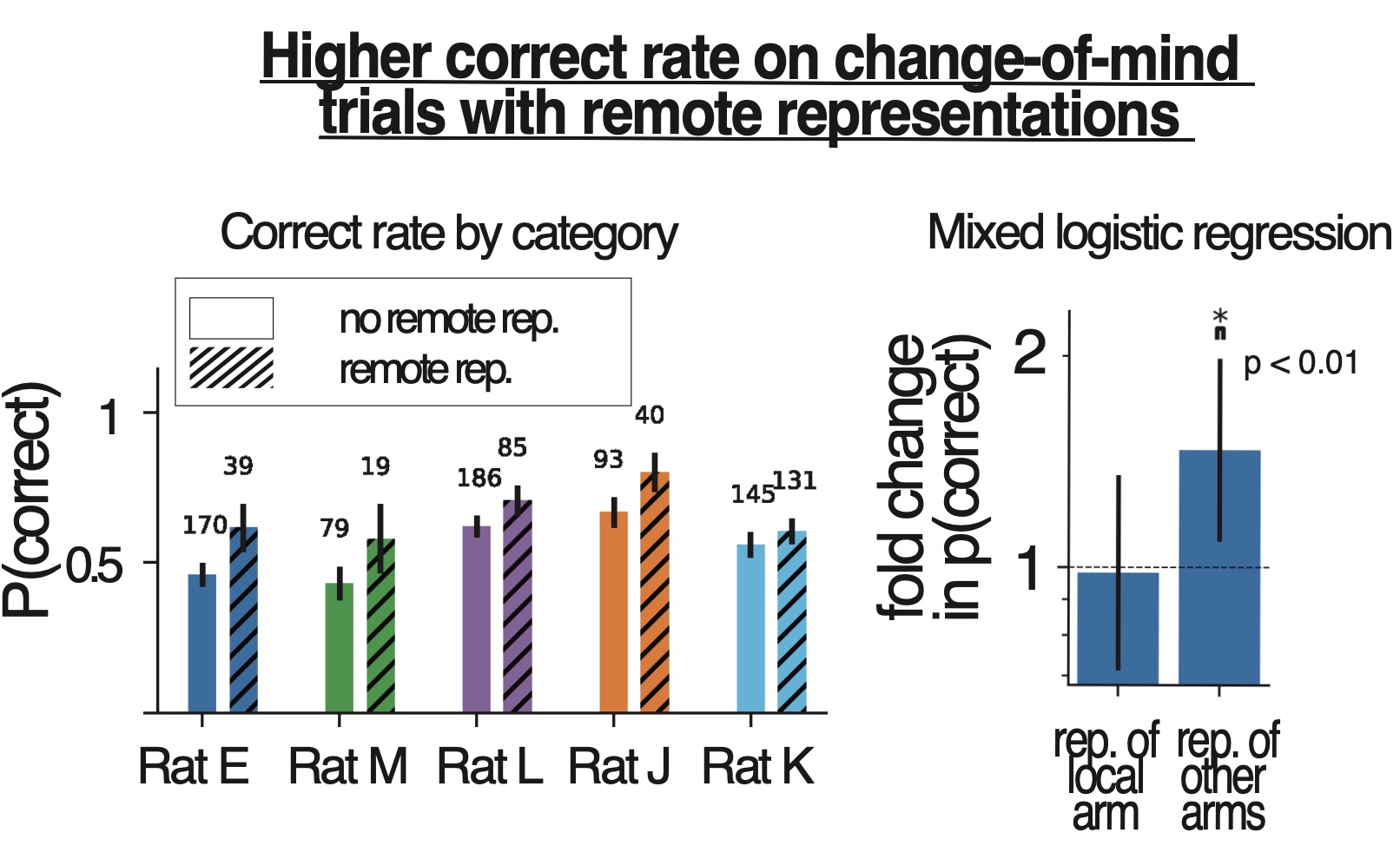

You can see that the hippocampus often represents other arm locations. It turns out that these representations are statistically predictive of where the animal will go next (Mixed logistic regression, fold change 1.9, p < 0.0001).

Remote representations predict improved task performance

Another intriguing finding is that on these trials where the hippocampus have explored other arm options, animals on average make better subsequent choice. The effect size is about 1.4. Meaning given a baseline of getting right at probability of p, with some help of hippocampus exploring remote options, the probability of getting right jumps to be 1.4 * p. For example, given a baseline of getting right at probability of 0.5, with some help of hippocampus exploring remote options, the probability of getting right becomes 0.7.

Meanwhile, we are exploring if the gaze of the animal is related to this mental exploration of options. Please stay tuned for the final paper!

- Written by Shijie Gu, Oct 19, 2025 and Nov 13, 2025.

- Figures edited by Loren Frank, Nov 11, 2025.

- Text edited by Vanessa Bender, Nov 13, 2025.